Chicago has long been known as a place where there are no coincidences. But one of the biggest political racketeering cases in the city’s history — USA v. Michael J. Madigan — actually did land randomly at the bench of a judge nicknamed the “Son of RICO.”

U.S. District Judge John Robert Blakey turned 5 the year his father G. Robert Blakey’s revolutionary legislation, the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations statute, was signed into law.

The statute, designed to go after organized crime, made the elder Blakey into legal royalty. His son chose a legal path that, for the most part, kept his boots on the ground. “Jack” Blakey spent most of his career as a prosecutor, both for the federal government and at Cook County’s rough-and-tumble criminal courthouse.

But he kept in touch with the RICO legacy, helping draft the Illinois racketeering legislation that focused on powerful street gangs. And in 2014, as a nominee for the federal judgeship, his introduction to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee also mentioned his famous father.

“It is a twofer,” then-Sen. Mark Kirk, R-Illinois, said of Blakey. “We are getting Jack and his dad. … If there is any state in the union that needs experts on RICO, it is Illinois.”

This week, Madigan — a former Illinois political powerhouse fallen spectacularly from grace — is going to trial on RICO charges he abused his considerable clout for personal gain. The government accuses him and co-defendant Michael McClain of bribery, wire fraud and conspiracy. But the backbone of the indictment is racketeering. And presiding from the bench will be Blakey, who sometimes seems to know RICO even better than the attorneys in front of him.

The world RICO built

With the 1970 legislation initially aimed at mobsters, it made it possible for prosecutors to hold high-level bosses just as accountable for ordering an illegal act as the underlings who carried it out.

It became an extraordinarily powerful tool, one that is credited with hobbling the Mafia across the country. And its basic principle — charging broad conspiracies — has expanded far beyond mob cases. RICO has been used to go after street gangs, sex cultists, college admissions cheats, international soccer officials and R. Kelly.

In the Madigan case, prosecutors have used it to target alleged public corruption. Madigan, the Southwest Side Democrat who reigned as speaker of the Illinois House for decades, is accused alongside McClain, a lobbyist and longtime ally, of running their government and political operations like a criminal enterprise. Their goal, prosecutors have said, was to increase Madigan’s clout and enrich himself and his associates.

Madigan and McClain have pleaded not guilty, and over two-plus years of pretrial hearings they have tried to attack the charges and the potential evidence on a microscopic level. Blakey has declined to grant their bigger requests and the indictment remains intact.

-

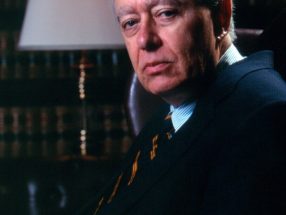

Former Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan walks across Dearborn Street toward the Dirksen U.S. Courthouse on Oct. 2, 2024, for the final in-person hearing before his Oct. 8 trial begins. (Antonio Perez/Chicago Tribune)

-

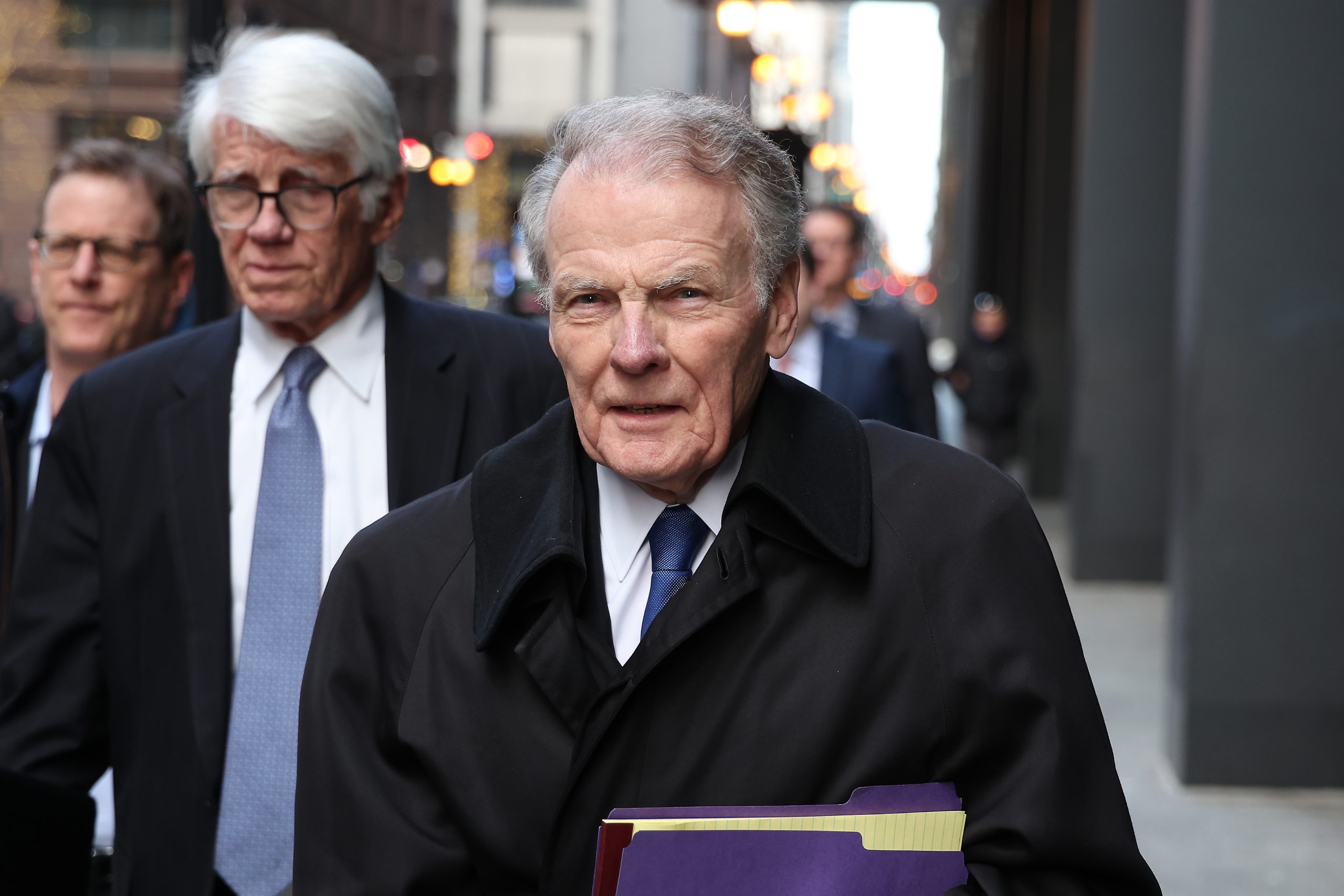

Former Speaker of the Illinois House Michael Madigan is seen during a break in his hearing held at Dirksen U.S. Courthouse on Sept. 16, 2024. (Antonio Perez/Chicago Tribune)

-

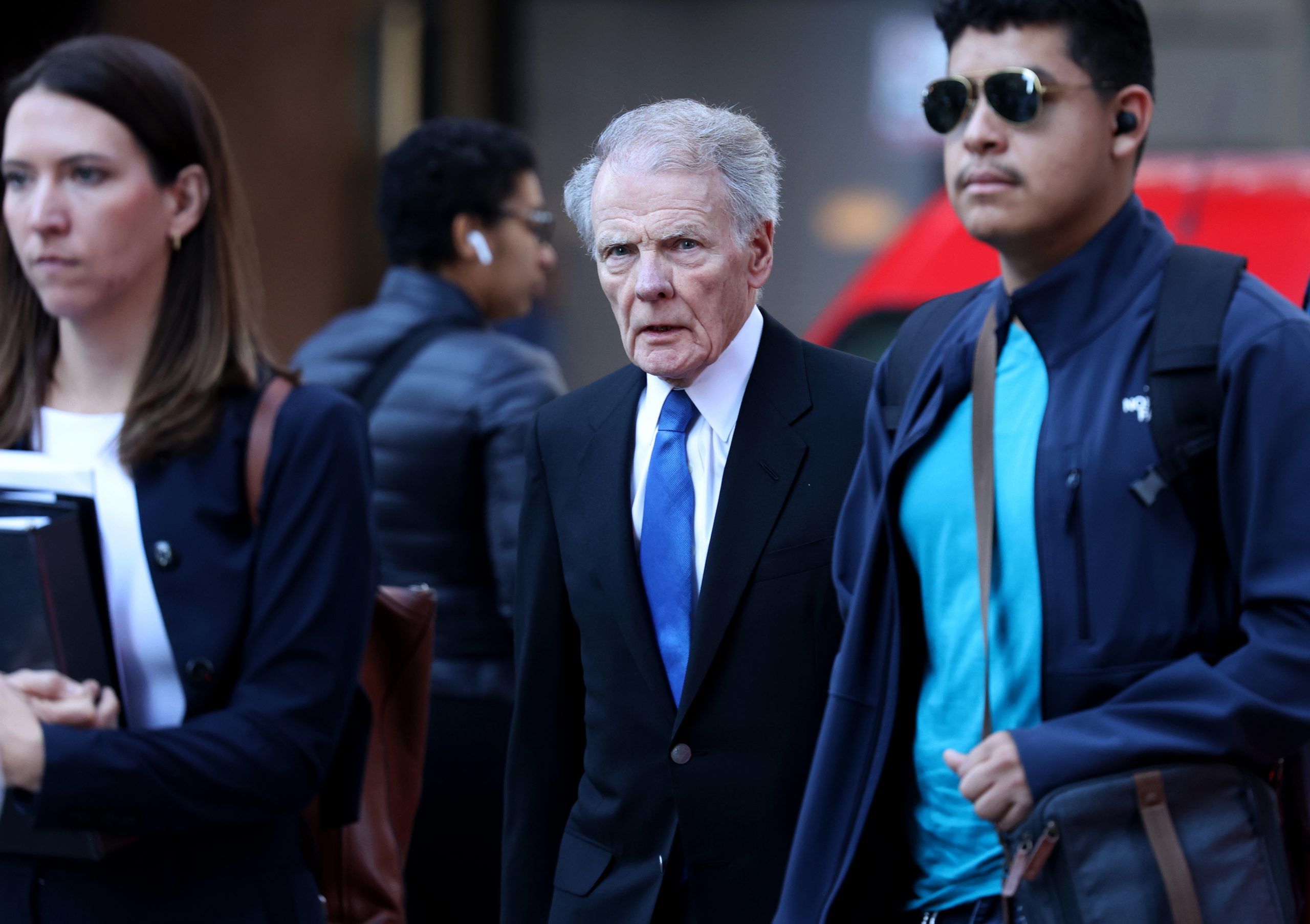

Former Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan, second from left, arrives at the Dirksen U.S. Courthouse in Chicago with his legal defense team on July 16, 2024, for a hearing on pretrial motions in his racketeering case. (Terrence Antonio James/Chicago Tribune)

-

Former Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan, foreground, leaves the Dirksen U.S. Courthouse in Chicago on Jan. 3, 2024. (Terrence Antonio James/Chicago Tribune)

-

Jose M. Osorio / Chicago Tribune

Former Illinois Speaker of the House Michael Madigan arrives to his office in Chicago on Oct. 18, 2021.

-

Brian Cassella / Chicago Tribune

Former Illinois Speaker Michael Madigan departs from his lawyers’ office, March 9, 2022, after making his first virtual court appearance for his indictment.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak / Chicago Tribune

Speaker Michael Madigan arrives for the Illinois House Democratic caucus during a spring session of the General Assembly at the Illinois Capitol in Springfield in 2019.

-

Antonio Perez/Chicago Tribune

Former Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan walks on his second-floor patio at his Chicago home on March 3, 2022.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan listens Dec. 3, 2013, after introducing a bill to overhaul the state government worker pension system.

-

Jose M. Osorio / Chicago Tribune

Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan after a meeting with Gov.-elect Bruce Rauner and Senate President John Cullerton in Chicago on Nov. 13, 2014.

-

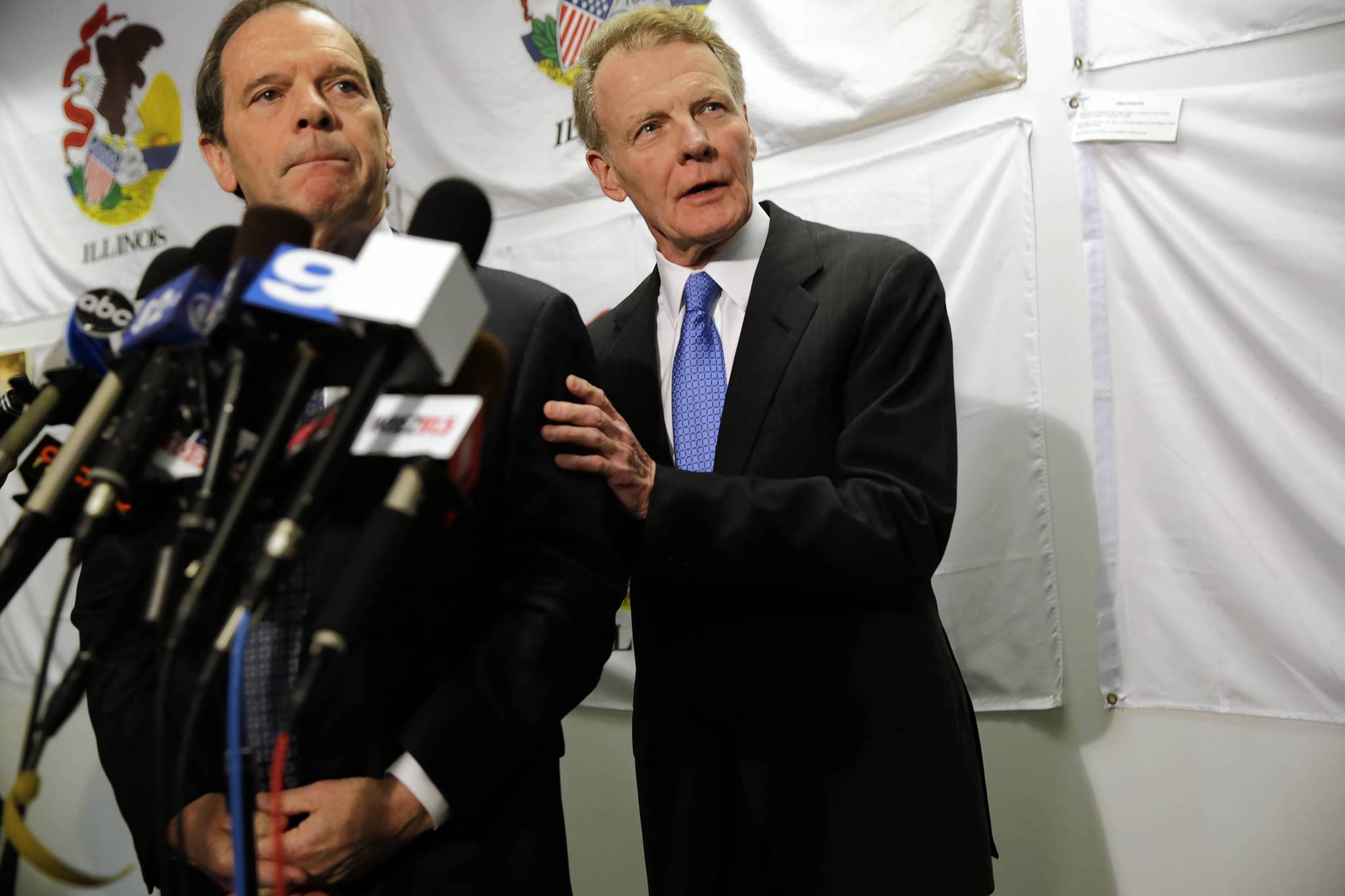

Terrence Antonio James / Chicago Tribune

After a meeting with then-Gov. Bruce Rauner (not shown), Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan prepares to address the media at the State of Illinois Building in Chicago on Dec. 6, 2016.

-

E. Jason Wambsgans / Chicago Tribune

Speaker Michael Madigan stands over lawmakers on the House floor before Gov. J.B. Pritzker delivers his first budget address Feb. 20, 2019, at the Illinois State Capitol in Springfield.

-

Chuck Berman, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan answers questions at a press availability Jan. 24, 2012, after he addressed the fifth annual Elmhurst College Governmental Forum.

-

Antonio Perez / Chicago Tribune

Michael Madigan arrives to his West Lawn home on March 2, 2022 before it was announced he was indicted on federal racketeering charges.

-

John J. Kim / Chicago Tribune

A broadcast news reporter knocks on the door at the home of former Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan in the West Lawn neighborhood on March 2, 2022, in Chicago.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan introduces the pension reform bill Dec. 3, 2013.

-

Antonio Perez / Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, left, speaks with House Majority Leader Rep. Greg Harris before Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s budget address in Springfield on Feb. 19, 2020.

-

Brian Cassella / Chicago Tribune

Former Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan talks during a meeting where his replacement, Angie Guerrero-Cuellar, was chosen Feb. 25, 2021, at the Balzekas Museum in West Lawn.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak / Chicago Tribune

Speaker of the House Michael Madigan leaves after the Democratic Caucus on May 31, 2017.

-

Michael Tercha, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan talks with state Rep. Elaine Nekritz as they prepare to present a state pension reform plan to the Personnel and Pensions Committee on May 29, 2012.

-

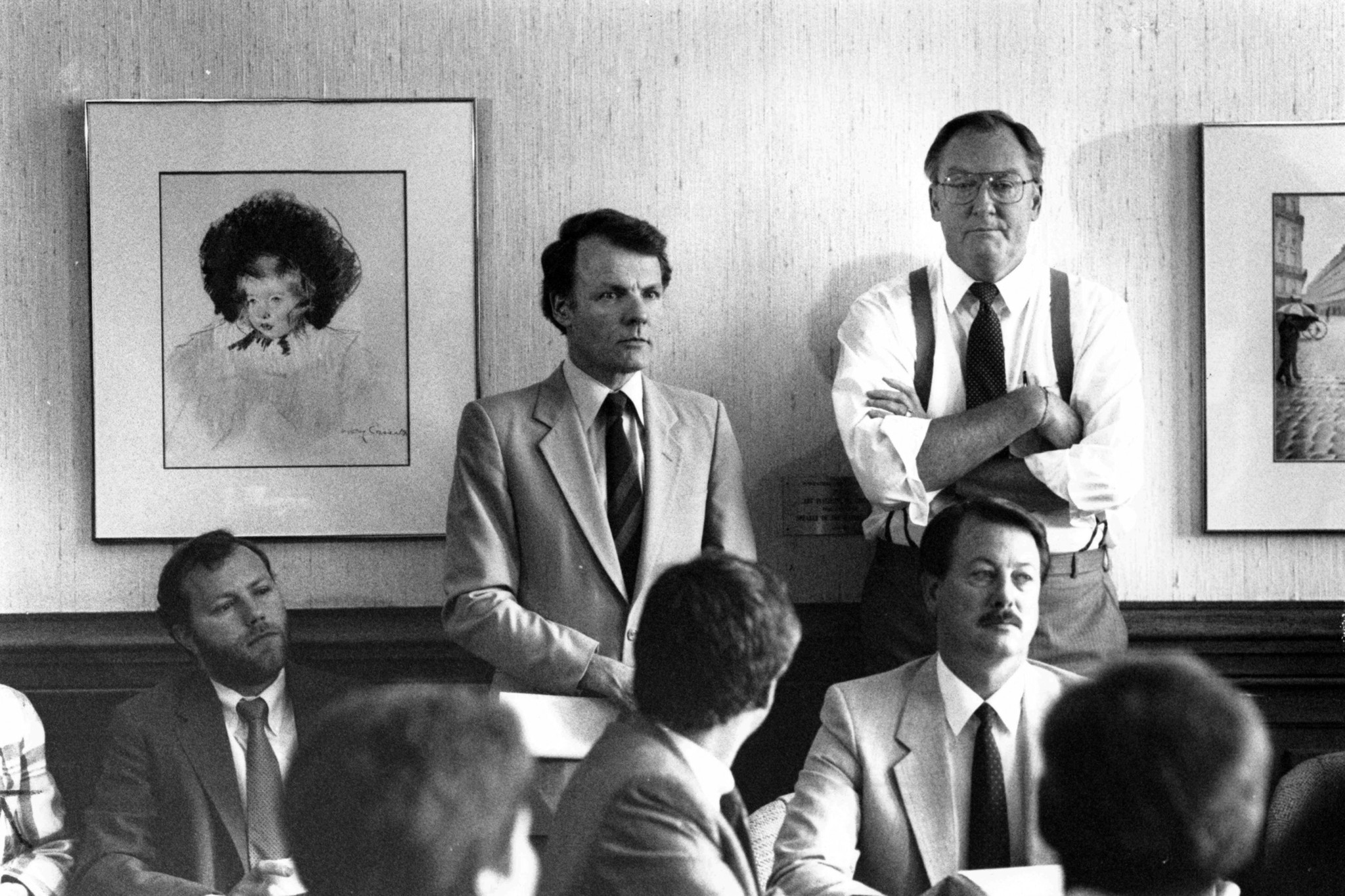

William DeShazer, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, center, listens after speaking to the Personnel and Pensions Committee meeting May 26, 2011.

-

Charles Osgood, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan convenes the House on June 26, 2004.

-

Abel Uribe, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan listens to the debate about Resolution 1650, which he co-sponsored, as the process of impeaching Gov. Rod Blagojevich begins Dec. 15, 2008.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak / Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan watches as the Illinois House votes on a bill raising statewide minimum wage during a session at the State Capitol in Springfield on Feb. 14, 2019.

-

Chris Walker, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan leaves his Capitol office Feb. 28, 2013.

-

Nancy Stone, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, from left, Gov. Pat Quinn and Senate leader John Cullerton sit next to one another Aug 19, 2009, at Governor’s Day at the Illinois State Fair.

-

Nancy Stone, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan waits for official notice from the Senate that they have voted to form a conference committee during a special session in Springfield on June 19, 2013.

-

Stacey Wescott, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, left, celebrates with state Rep. Jay Hoffman on July 24, 2004, after both houses of the legislature passed the 2005 budget after going 51 days into special session.

-

Abel Uribe, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, left, and Senate President John Cullerton confer March 18, 2009, as Gov. Pat Quinn delivers his proposal for the 2010 state budget in the House.

-

Michael Tercha, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan greets AFSCME’s Henry Bayer along with other opposition members before he presents a state pension reform plan to the Personnel and Pensions Committee on May 29, 2012.

-

John Lee, Chicago Tribune

Newly elected House GOP Leader Tom Cross, left, and House Speaker Michael Madigan chat Nov. 21, 2002, before the start of session at the Capitol in Springfield.

-

Michael Tercha, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan shares the stage with Gov. Rod Blagojevich and state Sen. Debbie Halvorson, D-Chicago Heights, on Aug. 15, 2007, at the Democratic rally at the Illinois State Fairgrounds for Governor’s Day in Springfield.

-

E. Jason Wambsgans / Chicago Tribune

Speaker of the House Michael Madigan on his 70th birthday on the House floor at the Illinois State Capitol in Springfield on April 19, 2012.

-

Charles Osgood, Chicago Tribune

Gov. Rod Blagojevich, from left, Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley and House Speaker Michael Madigan enjoy Democratic Day on Aug. 16, 2006, at the Illinois State Fair in Springfield

-

Brian Cassella / Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan speaks Aug. 17, 2017, at the annual Democratic Chairman’s Brunch in Springfield.

-

Jose M. Osorio, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, left, introduces newly elected Gov. Rod Blagojevich in the House gallery in Springfield on Dec. 4, 2002.

-

William DeShazer, Chicago Tribune

Speaker Michael Madigan oversees House proceedings Jan. 6, 2011, at the state Capitol.

-

Stacey Wescott / Chicago Tribune

Michael Madigan, then speaker of the Illinois House of Representatives, in the Capitol building in Springfield on Jan. 24, 2017.

-

Michael Tercha, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, D-Chicago, left, greets supporters as they arrive for the 32nd Annual Democratic Evening on the Lake fundraiser May 8, 2012, at Island Bay Yacht Club in Springfield

-

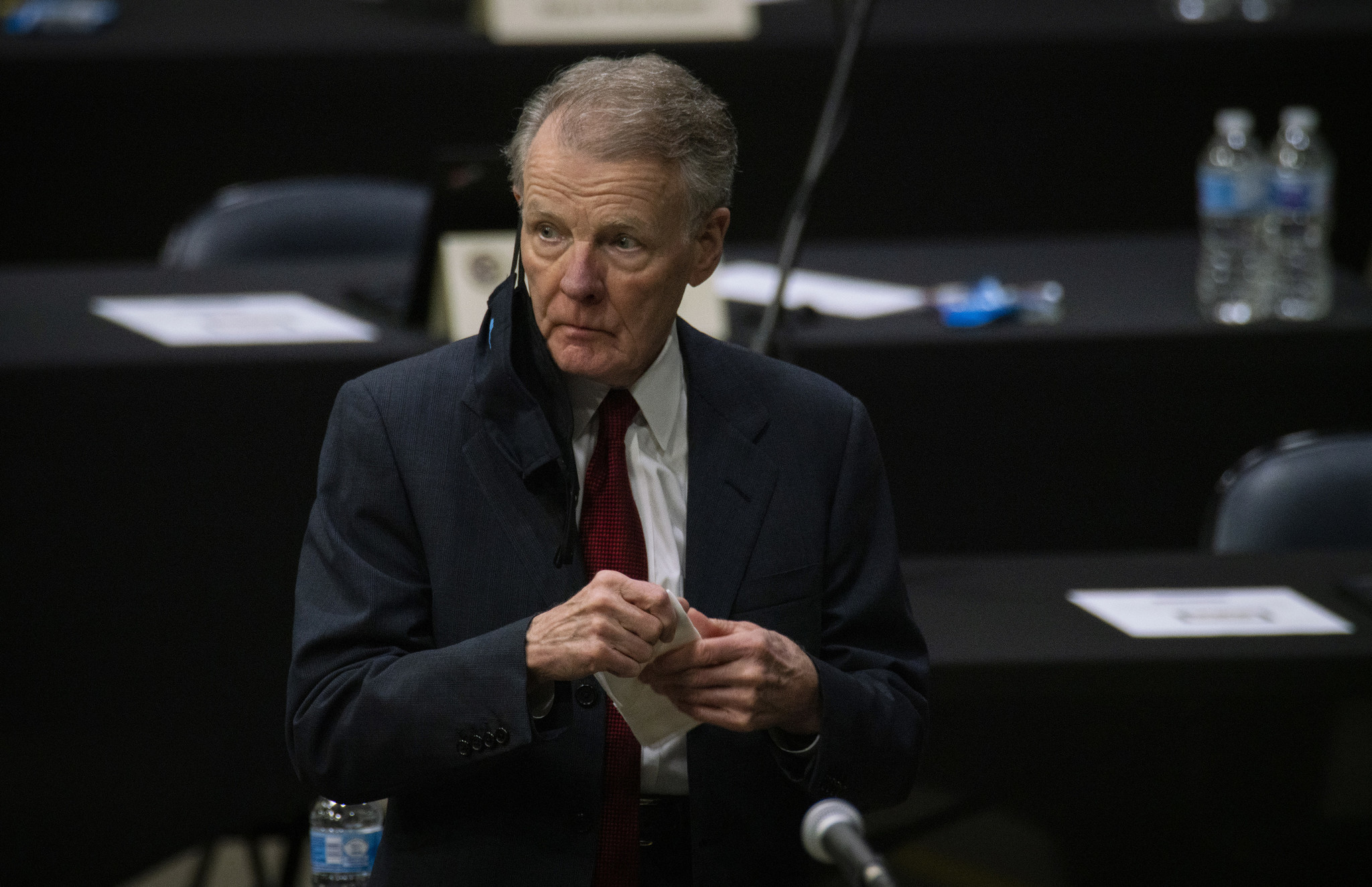

E. Jason Wambsgans / Chicago Tribune

Speaker Michael Madigan on the floor as the Illinois House of Representatives convenes at the Bank of Springfield Center on Jan. 8, 2021.

-

Abel Uribe, Chicago Tribune

Rod Blagojevich, center, shakes hands with Michael Madigan after his speech at the Illinois State Fair on Aug. 15, 2002.

-

Charles Osgood, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, right, tries to get the attention of the acting speaker June 24, 2004, with the help of his spokesman, Steve Brown, left.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak / Chicago Tribune

Michael Madigan speaking to the media on June 30, 2015.

-

Antonio Perez / Chicago Tribune

Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan and his wife, Illinois Arts Council Agency Chairwoman Shirley Madigan, kiss after she testified in support of the Obama presidential library being located in Chicago on April 17, 2014.

-

Abel Uribe, Chicago Tribune

Gov. Pat Quinn, from left, House Speaker Michael Madigan, Ald. Ed Burke, and state Sen. Martin Sandoval attend a groundbreaking for a new UNO high school July 12, 2012, in Chicago.

-

Michael Tercha, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, center, along with his research and appropriations director, John Lowder, left, and state Rep. Elaine Nekritz, D-Northbrook, presents a state pension reform plan to the Personnel and Pensions Committee on May 29, 2012.

-

E. Jason Wambsgans / Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan congratulates Gov. J.B. Pritzker after Pritzker’s first budget address at the Illinois State Capitol in 2019.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan talks to Rep. Carol Sente on Dec. 3, 2013, after a vote on a bill to overhaul the state government worker pension system.

-

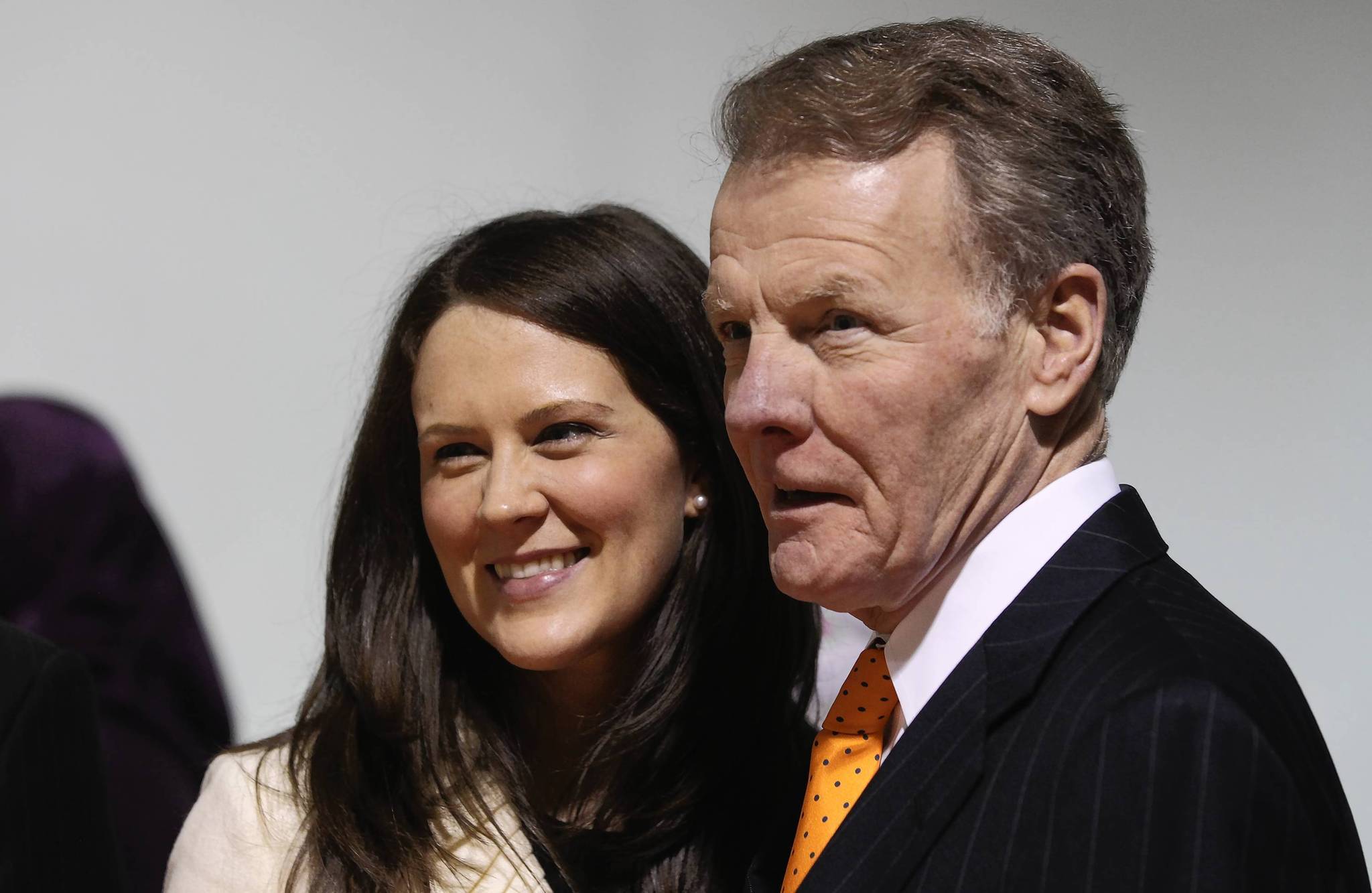

Heather Stone, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan and his wife, Shirley, join supporters as their daughter Lisa Madigan kicks off her campaign for state attorney general Dec. 2, 2001.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak / Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan talks with House Republican Leader Jim Durkin before a debate at Illinois House to vote on a bill raising statewide minimum wage during a session at the State Capitol in Springfield on Feb. 14, 2019.

-

Antonio Perez, Chicago Tribune

Michael Madigan and daughter Nicole tour the Science Academy of Chicago during its grand opening event March 8, 2013, in Mount Prospect.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak / Chicago Tribune

Senate President John Cullerton and House Speaker Michael Madigan talk to the media after meeting with Gov. Bruce Rauner on the last day of the Illinois General Assembly at the State Capitol in Springfield on May 31, 2016.

-

E. Jason Wambsgans / Chicago Tribune

Speaker Michael Madigan works the floor as the Illinois House convenes at the Bank of Springfield Center on Jan. 8, 2021.

-

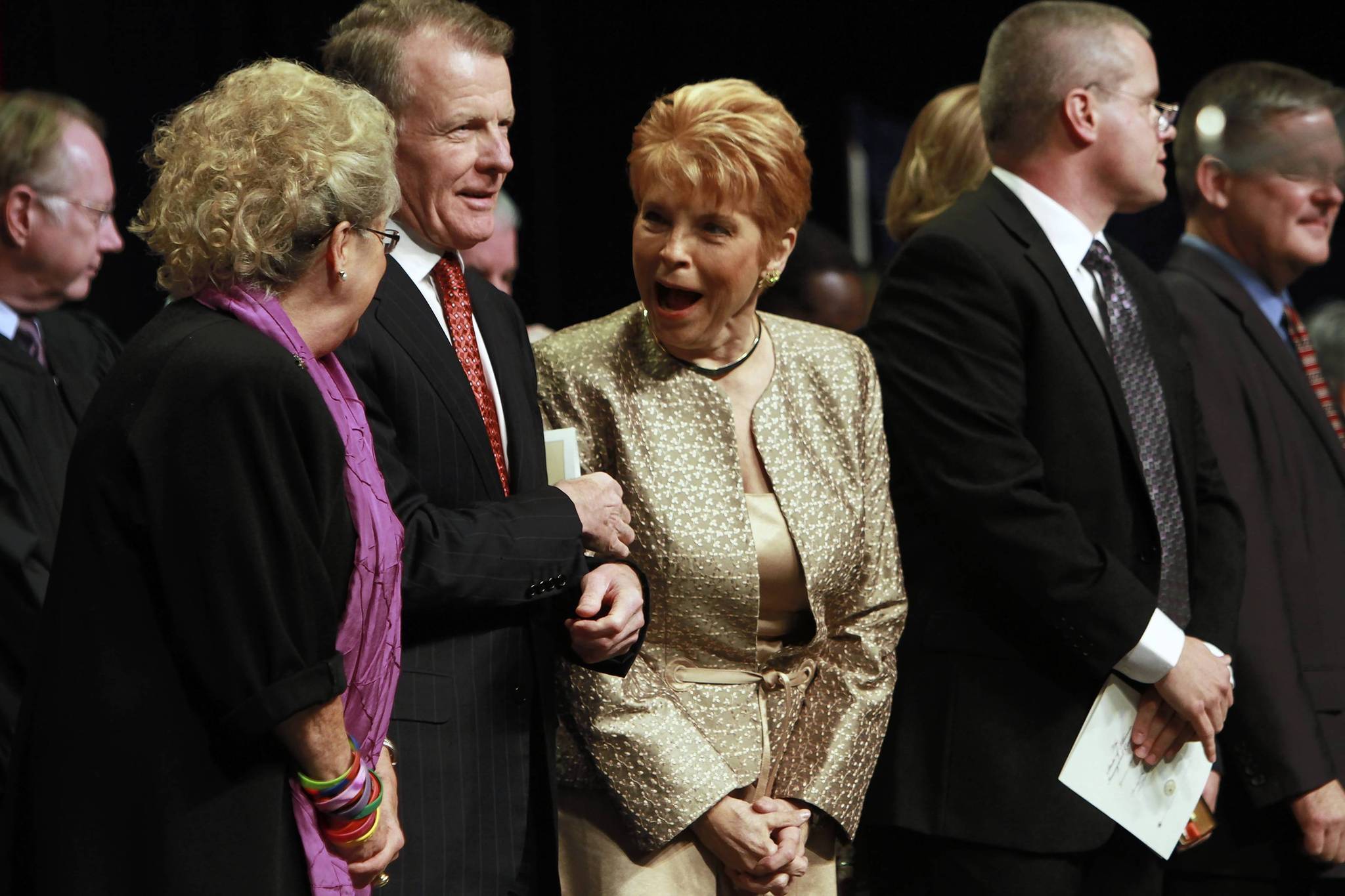

Michael Tercha, Chicago Tribune

Illinois Comptroller Judy Baar Topinka, center, talks with House Speaker Michael Madigan and his wife, Shirley, during the inaugural ceremony for constitutional officers on Jan. 10, 2011.

-

Seth Perlman / AP

House Speaker Michael Madigan and Senate President John Cullerton on the floor of the General Assembly in Springfield on June 16, 2015.

-

Michael Tercha, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, left, greets Gov. Rod Blagojevich on Aug. 18, 2004, during the Governor’s Day Rally at the Illinois State Fairgrounds.

-

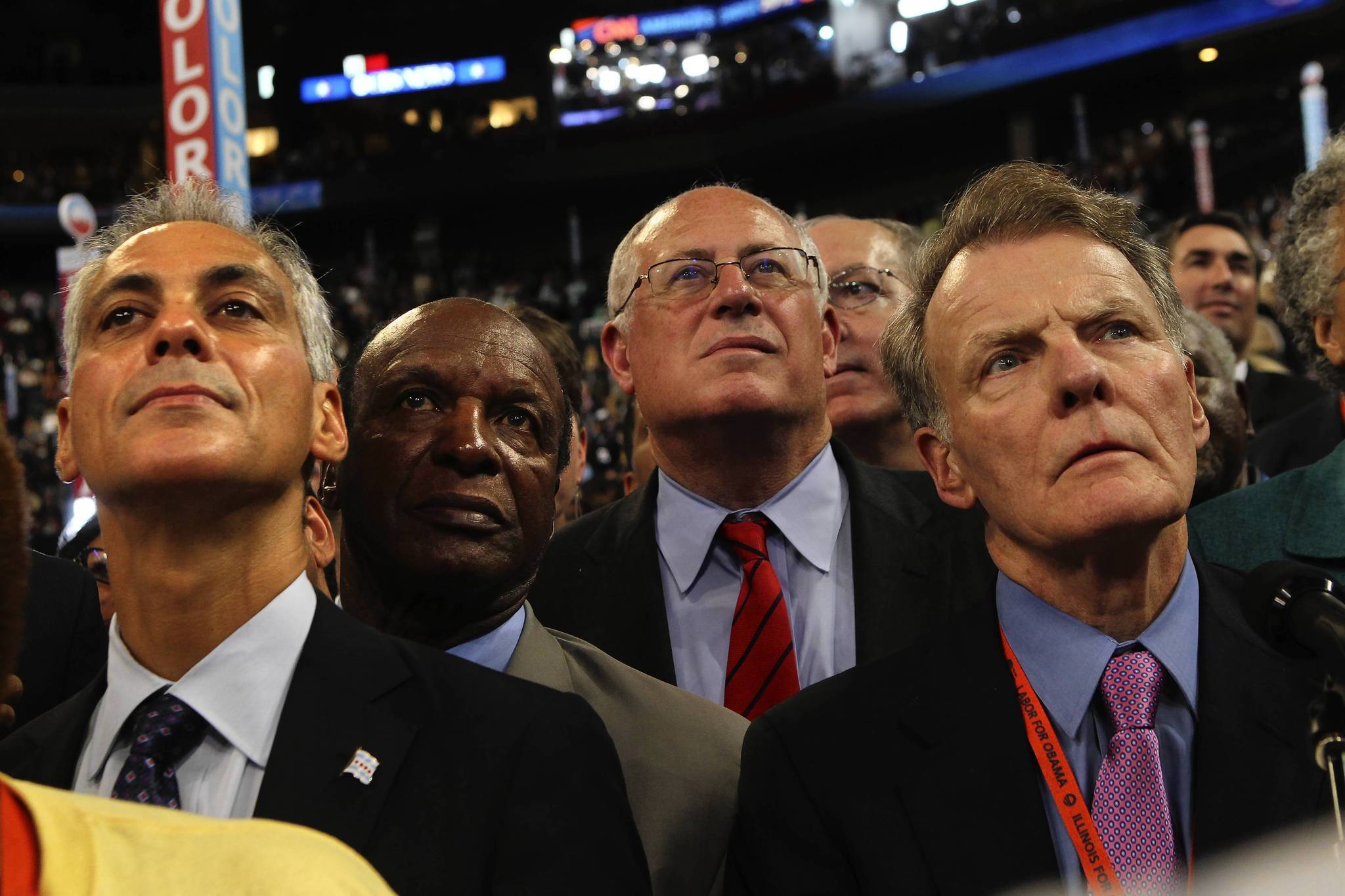

Nancy Stone, Chicago Tribune

Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel, from left, Secretary of State Jesse White, Gov. Pat Quinn and House Speaker Michael Madigan are represented in the roll call vote for Barack Obama at the Democratic National Convention on Sept. 5, 2012, in Charlotte, N.C.

-

Terrence Antonio James, Chicago Tribune

Gov. Pat Quinn, left, and House Speaker Michael Madigan testify on campaign finance reform May 29, 2009, in front of a House committee at the Capitol in Springfield.

-

Chris Walker, Chicago Tribune

As Illinois legislators continued work on a state budget, House Speaker Michael Madigan took time to attend an AFL-CIO labor rally April 24, 2002, at the Capitol.

-

Michael Tercha, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, left, and Senate President John Cullerton confer before Gov. Pat Quinn delivers his budget address to a combined session of the Illinois Legislature on Feb. 16, 2011.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak / Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan during the General Assembly fall session on Dec. 3, 2014.

-

E. Jason Wambsgans / Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan appears on the floor as the Illinois House convenes at the Bank of Springfield Center on Jan. 8, 2021. Lawmakers returned for a lame-duck session that marks the first time they convened in Springfield since a May special session.

-

Chris Walker, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, right, talks with Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel in Gov. Pat Quinn’s office July 26, 2011, at the James R. Thompson Center.

-

José Moré, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan heads a committee hearing in January 2007 regarding a rate hike requested by ComEd.

-

Carl Wagner, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, right, talks with Earl Oliver, president and executive secretary-treasurer of the Chicago Regional Council of Carpenters, in Oliver’s office on Oct. 16, 1998.

-

Heather Stone, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan talks about the budget after meeting with the governor May 24, 2001, at the state Capitol in Springfield.

-

Michael Tercha, Chicago Tribune

Senate President John Cullerton, left, and House Speaker Michael Madigan tell a reporter there is no bad blood between them after a meeting with Gov. Pat Quinn on June 10, 2013, to discuss pension reform legislation.

-

Charles Osgood, Chicago Tribune

Gov. Rod Blagojevich greets House Speaker Michael Madigan and Senate President Emil Jones on Feb. 16, 2005, before his speech delivering his budget to a joint session in the House chambers.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak / Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan listens to a debate on the House floor in 2019.

-

Stacey Wescott / Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan in the State Capitol building in Springfield on Jan. 24, 2017.

-

Stacey Wescott / Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan, right, chats with Senate President John Cullerton before Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner gives his State of the State speech at the Illinois State Capitol on Jan. 31, 2018 in Springfield.

-

E. Jason Wambsgans, Chicago Tribune

Minority Leader Tom Cross, left, joined by Speaker Michael Madigan, presents pension reform legislation Dec. 15, 2011, before the House Personnel and Pensions Committee.

-

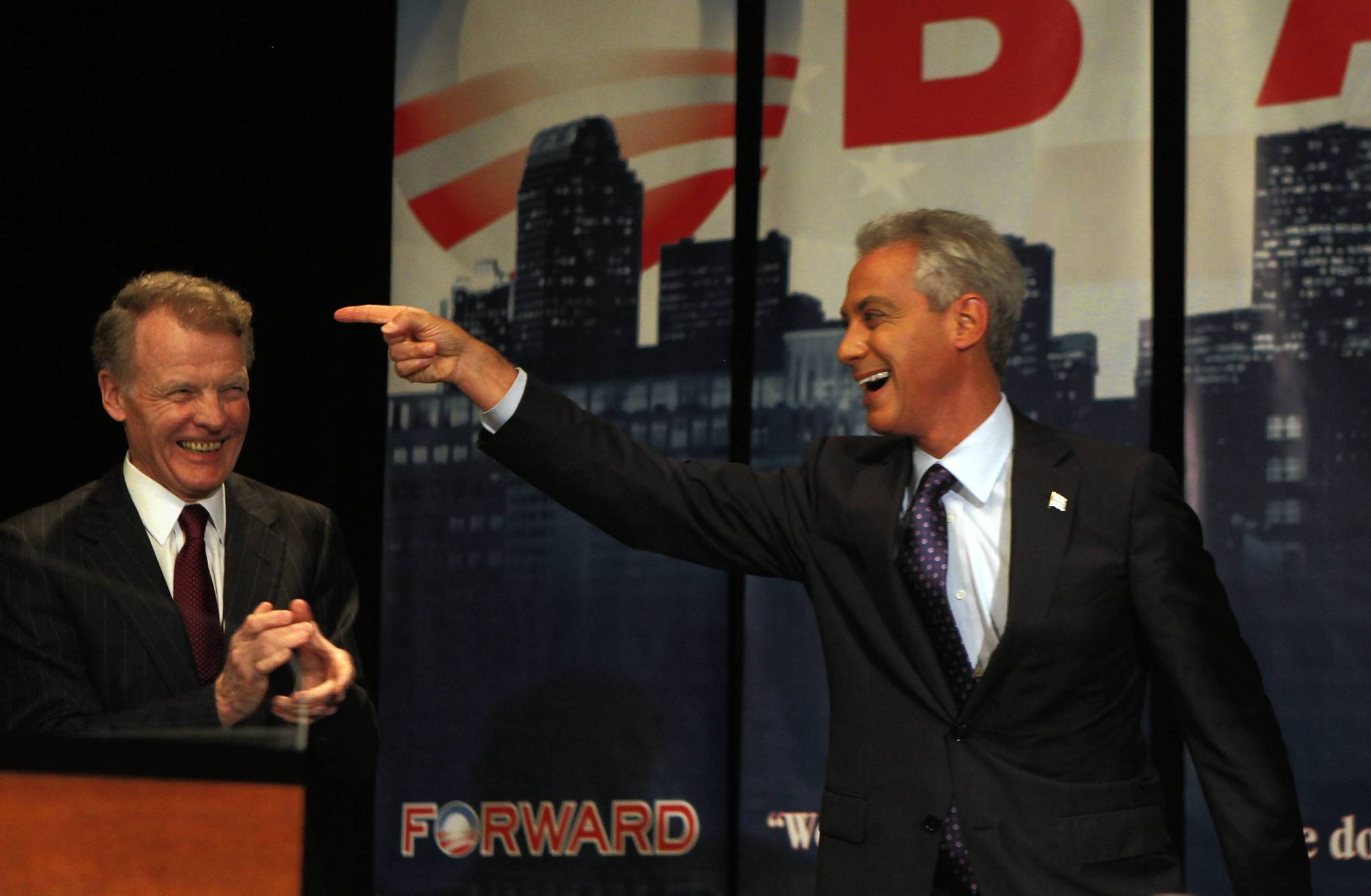

Nancy Stone, Chicago Tribune

Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel is applauded by House Speaker Michael Madigan Sept. 5, 2012, as he finishes speaking at the Illinois delegation breakfast in Charlotte, N.C.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak / Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan holds a news conference at the Capitol in Springfield on June 30, 2015.

-

Chris Walker, Chicago Tribune

Gov. George Ryan, left, leading a delegation of business, cultural and humanitarian leaders along with senior state officials on a trip to Cuba, joins in lunch conversation on the plane Oct. 23, 1999, with House Speaker Michael Madigan.

-

José Moré, Chicago Tribune

Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley, left, chats with House Speaker Michael Madigan as they look over the newly renovated House chambers May 16, 2007, in Springfield.

-

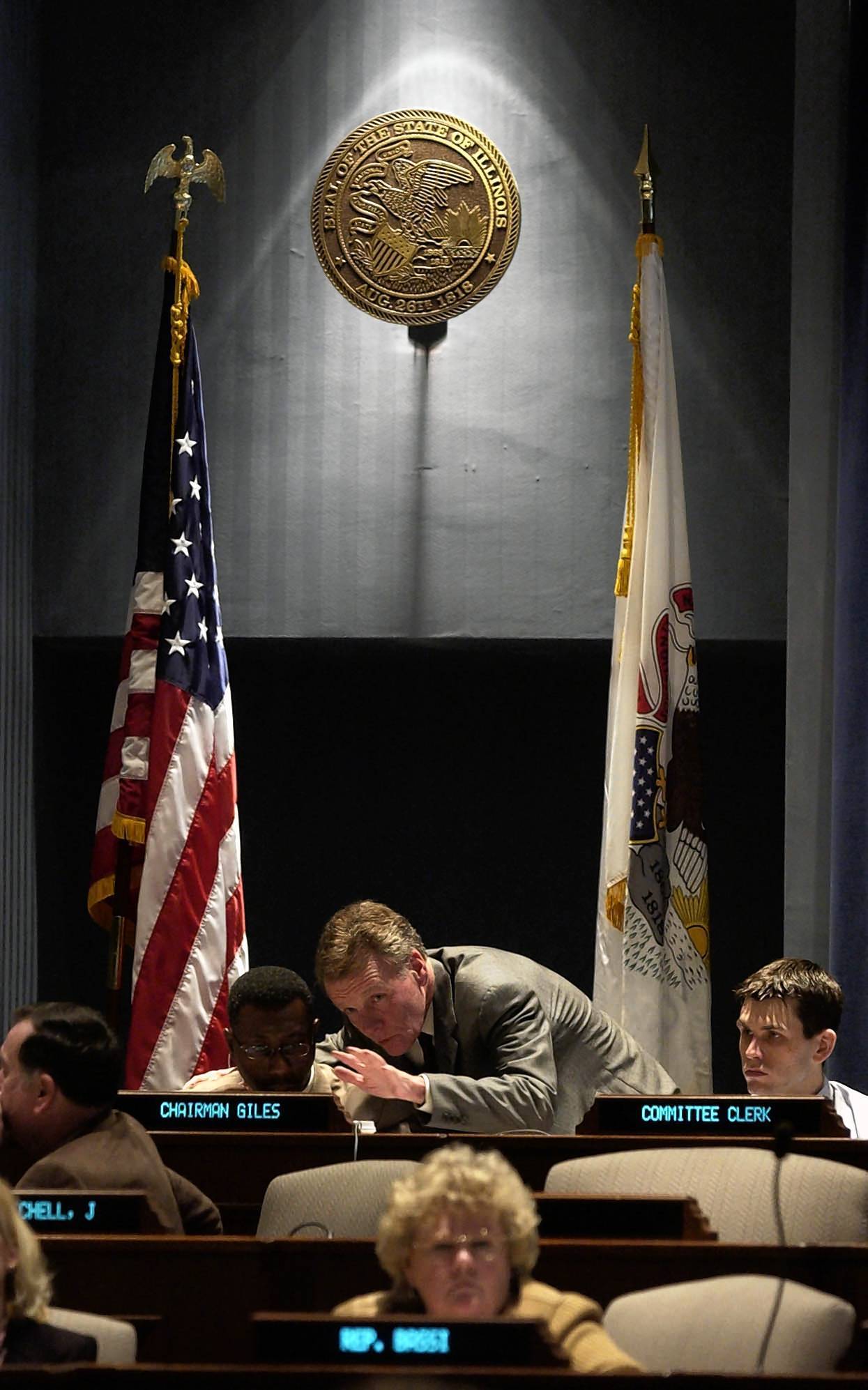

Abel Uribe, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan chats with Rep. Calvin Giles on March 24, 2004, during a hearing about the governor’s plan to take over the Illinois State Board of Education.

-

Scott Strazzante, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan acknowledges applause from Sen. Debbie Halvorson, foreground, and the rest of the Senate on May 31, 2003, at the state Capitol.

-

E. Jason Wambsgans, Chicago Tribune

Speaker Michael Madigan on the House floor May 31, 2013.

-

Zbigniew Bzdak, Chicago Tribune

House Speaker Michael Madigan walks through the state Capitol in Springfield on Dec. 3, 2013, to vote on a bill to overhaul the state government worker pension system.

-

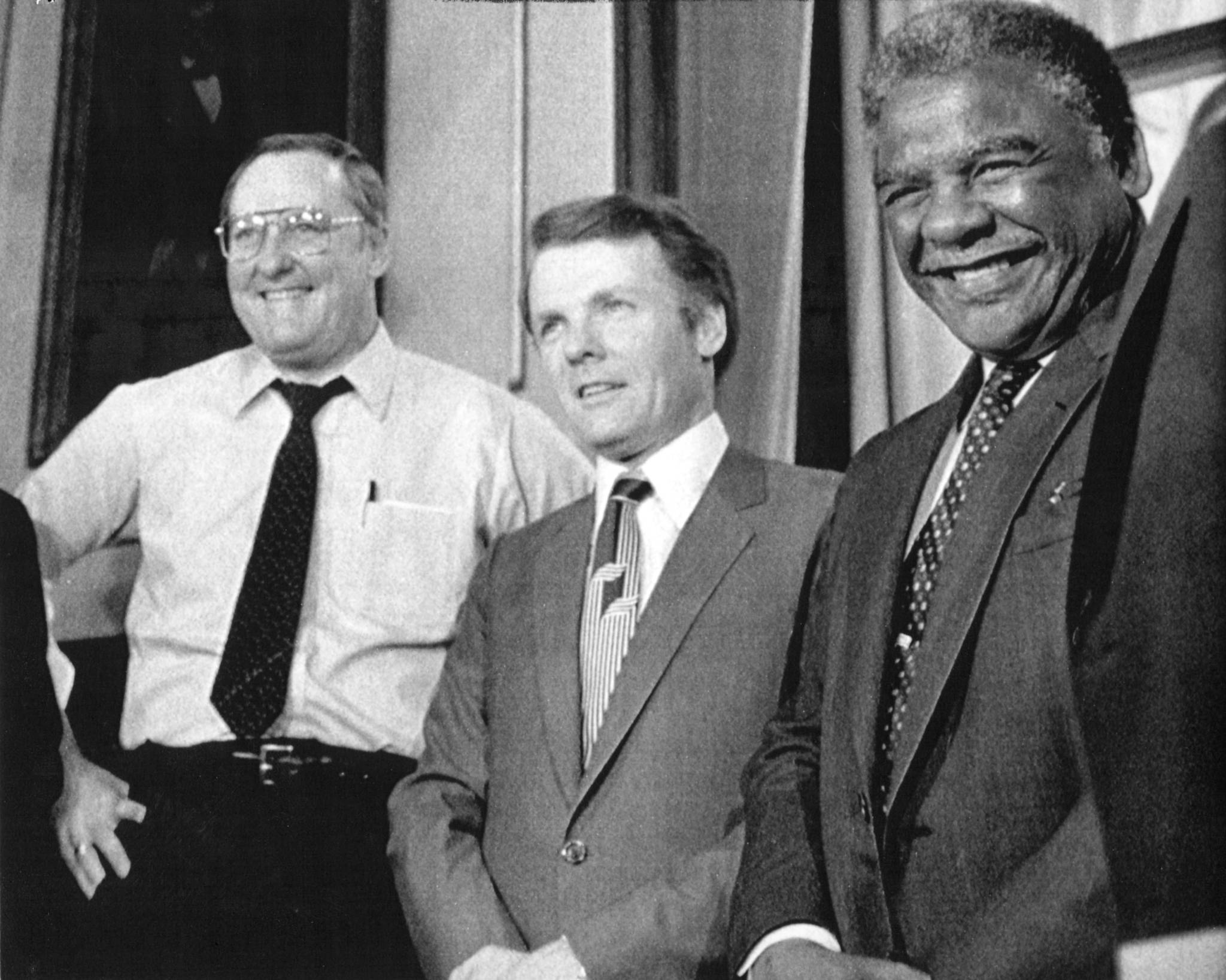

Chicago Tribune

Gov. James Thompson, from left, poses with House Speaker Michael Madigan and Mayor Harold Wahington on Oct. 19, 1983, before their meeting on the Regional Transportation Authority. They are trying to reach a deal on reorganization of the agency in exchange for a $75 million state subsidy.

-

Chicago Tribune

House Speaker George Ryan, from left, Senate President Phillip Rock, Chicago Mayor Jane Byrne, Sen. James Pate Philip and House Minority Leader Michael Madigan on June 4, 1981.

-

Chuck Berman / Chicago Tribune

Gov. James Thompson, right, and House Speaker Michael Madigan in Madigan’s office to work out school reform on July 1, 1988, in Springfield.

-

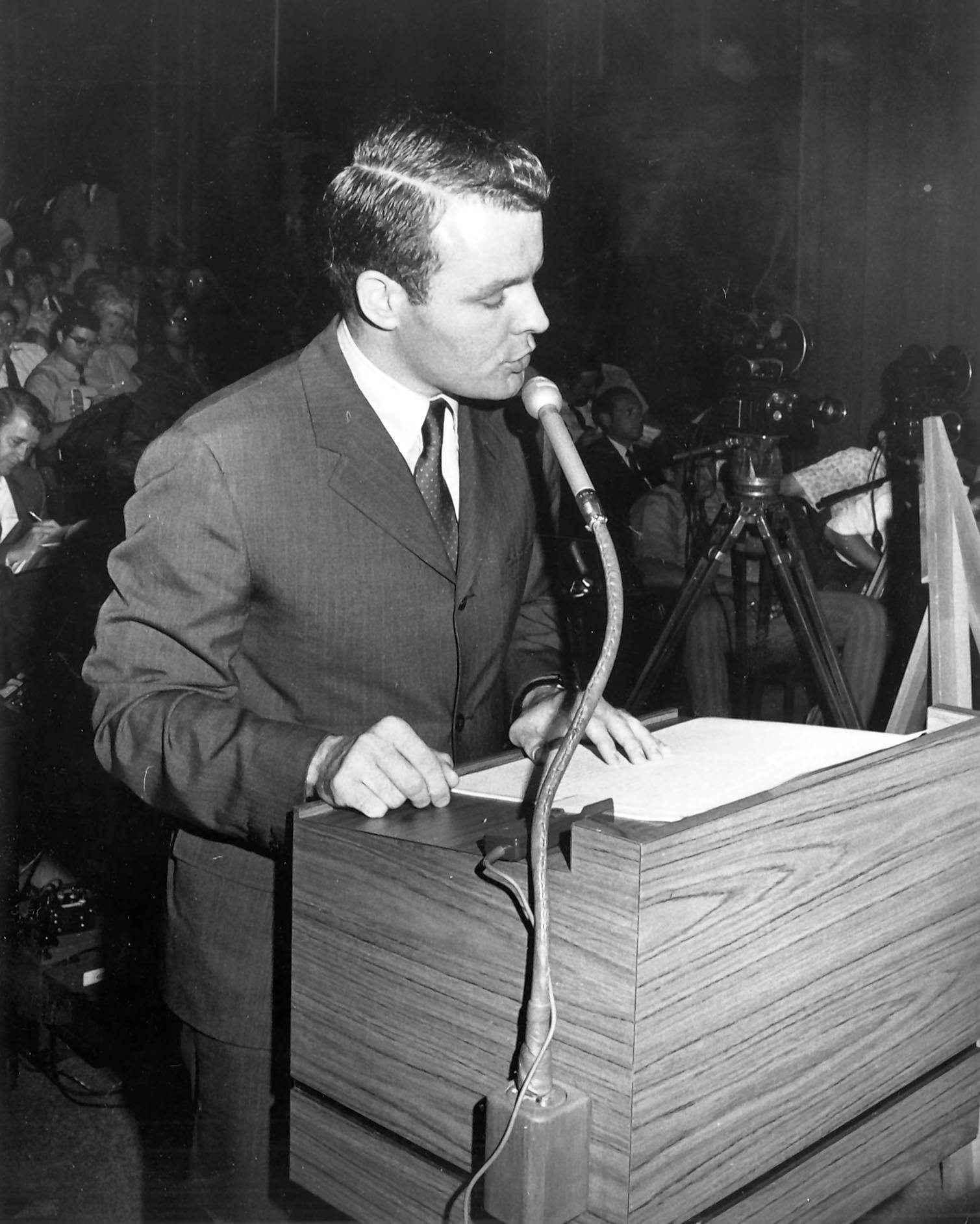

Alton Kaste, Chicago Tribune

Committeeman Michael Madigan, 13th Ward, speaks before the park board July 28, 1970.

-

Chicago Tribune

Committeeman Michael Madigan, circa 1970.

Former Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan walks across Dearborn Street toward the Dirksen U.S. Courthouse on Oct. 2, 2024, for the final in-person hearing before his Oct. 8 trial begins. (Antonio Perez/Chicago Tribune)

But defendants have won some of their arguments about what evidence jurors can hear. In a blow to prosecutors, for example, Blakey barred them from playing a potentially damning wiretapped conversation in which Madigan allegedly told McClain some of their friends had “made out like bandits” with the contracts they’d landed for them.

The trial is scheduled to begin Tuesday with jury selection, and proceedings are expected to last into December.

Blakey, according to attorneys who have practiced in front of him, is well-suited for complex RICO cases even apart from his family pedigree. He is quick-minded, they said, well-organized and has little patience for lateness or sloppy preparation.

In court, he is talkative and sometimes quippy, but rarely casual. He is not shy about interrupting or correcting attorneys. He doesn’t have much of a poker face, and even sitting on the bench he appears to be constantly moving: furrowing and unfurrowing his brow, rubbing his beard, talking with his hands.

Dramatic flair

The former theater major has an actor’s flair for an attention-grabbing one-liner, such as last month, when he point-blank asked Gangster Disciples founder Larry Hoover how many murders he was responsible for. Hoover’s attorney, who is seeking his release from a life sentence, later filed paperwork saying Blakey should recuse himself, saying his comments were “vaguely intimidating,” “entirely inappropriate” and showed bias.

In some ways, Blakey is the polar opposite of the late U.S. District Judge Harry Leinenweber, who oversaw the Madigan-adjacent “ComEd Four” trial last year in his typically laid back style and gave the lawyers, including McClain attorney Patrick Cotter, great leeway in making their arguments.

At one recent hearing, Blakey abruptly cut off Cotter when he felt the high-energy attorney was being a bit too disruptive.

“Counsel, counsel,” Blakey said. “I want to make sure we get great habits now, because we are going to be on trial together for a long period of time. When I start talking, you have to stop, OK? When the witness is giving you an answer, you cannot talk over the witness, all right?”

Tony Thedford, a defense attorney who represented a client in a racketeering trial before Blakey last year, told the Tribune he found the judge to be “extremely knowledgeable” in that area of the law. Federal RICO cases require a working knowledge of state statutes, so Blakey’s time as a Cook County prosecutor likely helped him, Thedford said.

“You have to be ambidextrous when it comes to RICO,” he said.

Attorney Jonathan Bedi said Blakey is “committed to efficiency” but also thoughtful, recalling sentencing hearings where Blakey seemed to truly listen to what the defendants had to say.

“I think he takes time to understand the complexities of the law but also, more importantly, the human side behind each defendant,” Bedi said.

Attorneys in front of Blakey should prepare for the judge to be an active participant, asking questions and challenging them, Thedford said.

“You’ve got to be nimble on your feet,” Thedford said. “You’d better be prepared walking into that courtroom. You better be prepared. Whatever your point of view is, whatever argument you want to make … you will be exposed if you are not.”

Blakey was born in 1965 in South Bend, Indiana, He grew up in a thoroughly Notre Dame family: Blakey’s father got his undergraduate and law degrees there, and was a prominent law professor there before receiving emeritus status in 2012. In time, Blakey and all seven of his siblings would attend the university. Blakey has said there was no real question of him going anywhere else: “It was the only place I wanted to go and the only place I applied,” he told a school publication in 2012.

He studied theater as an undergraduate, which attorneys who practice before him are not surprised to hear. Every courtroom, after all, is a stage. No matter how serious the legal issues, there is always an element of performance.

Blakey began acting in high school and went on to star in student productions at Notre Dame, including “King Lear.” After graduation, he trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art.

But soon, as Notre Dame has characterized it, he felt a call to public service. He went back to South Bend for law school, and his two Notre Dame degrees make him, in the school’s parlance, a “double domer.”

Trial work, he found, was not terribly different from the stage.

“You understand the basics of good storytelling. You understand what the important part of a narrative is and how it relates to your audience,” he told a Notre Dame publication in 2015. “That’s what lawyers do.”

The background in drama shows through, Bedi said.

“I think you can sometimes see that with his sense of humor, comedic timing,” Bedi said. “A trial is theater, so it makes sense.”

Legal rise

After earning his law degree, Blakey clerked for a federal judge in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, worked as a researcher for his father, and spent time at a downtown Chicago law firm.

In 1996 he began work as a Cook County assistant state’s attorney, including as a member of the prosecution team in the case of notorious Mafia hit man Harry “The Hook” Aleman.

Blakey later became a federal prosecutor in Miami, where his work included a RICO investigation targeting the Cuban Mafia; in 2004 he transferred closer to home, to work at the U.S. attorney’s office in Chicago.

In 2009, then-State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez tapped him to bring some federal flavor to Cook County courts.

She named Blakey head of the Special Prosecutions Bureau, which handles specialized or particularly complex cases. His first mandate, she told reporters, was to draft legislation that would give state prosecutors more power to go after public corruption — a category of crimes largely handled by the feds.

Blakey’s efforts led to Illinois’ own RICO statute, which passed in 2012.

But the bill only gained real support in the state legislature after lawmakers rewrote the language specifically so that it only applies to street gangs — not labor unions or political organizations with a clout-heavy constituency.

Still, it was a coup for Blakey, who told reporters as the bill awaited the governor’s signature that he saw it as a powerful tool.

“With a racketeering case, instead of just peeking through the keyhole and seeing one shooting, you get to open up the door and show a jury everything that led up to that shooting,” Blakey said in 2012.

Since then, only two RICO cases have been brought by Cook County prosecutors: a 2013 case against West Side gang the Black Souls, and a 2014 case charging an Outfit-connected burglary ring.

No other RICO prosecutions have been brought in Cook County, according to a spokeswoman for State’s Attorney Kim Foxx’s office.

Blakey’s second stint as a Cook County prosecutor lasted about five years, during which he became one of Alvarez’s top advisers and helped navigate her administration through what seemed like an endless parade of scandals and heater cases.

Blakey took point on Cook County’s first-ever prosecution under the Illinois terrorism statute: the “NATO 3” case. Three men were accused of plotting to attack police stations, Barack Obama’s campaign headquarters and then-mayor Rahm Emanuel’s home in the days leading up to the 2012 NATO summit in Chicago.

They were on, Blakey said in court, a “mission of hate,” hoping to send a “wake-up call for their twisted, anarchist revolution.”

Defense attorneys, meanwhile, characterized the men as simply foolish, drunk or stoned simpletons who were manipulated by undercover cops into making Molotov cocktails.

The weekslong trial was hotly contested. In the end, jurors acquitted them of terrorism-related charges, convicting instead on less serious counts related to making explosives and misdemeanor mob action.

The split verdict was widely seen as a major loss for prosecutors, a characterization Alvarez rejected, maintaining that she would bring the charges again “with no apologies and no second-guessing” and noting that the explosives convictions carried real prison time.

Blakey also found himself immersed in a major heater case after the Chicago Sun-Times in 2011 began its investigative series looking into the death of David Koschman, who was punched during a 2004 drunken Rush Street altercation with a nephew then-Mayor Richard Daley and suffered fatal head injuries when he fell, Alvarez made Blakey her point person in the politically charged reinvestigation of the case.

Alvarez unsuccessfully fought Koschman’s mother’s request for a special prosecutor to reinvestigate her son’s death. The state’s attorney insisted her office was taking an even-handed look at the evidence, even though it had twice concluded there was insufficient evidence to charge Daley’s nephew, Richard Vanecko.

Blakey was among several of Alvarez’s top advisers who sat down with the Tribune in 2012 to talk about the case, saying they saw no issue with the way the lead prosecutor, Darren O’Brien, had handled it in 2004.

According to Alvarez’s team, at that time there was no admissible evidence that could have been used to file charges, including a positive identification of Vanecko as the one who threw the fatal punch.

Days after that interview, then-Cook County Judge Michael Toomin appointed Winston & Strawn partner Dan Webb as a special prosecutor. In his strongly worded ruling, Toomin criticized Alvarez for seeking to “denigrate the evidence against Vanecko” and going out of her way to find “legal justification for Vanecko’s use of deadly force.”

Vanecko meanwhile, was charged with involuntary manslaughter, pleaded guilty in 2014 and was sentenced to 60 days in jail and 30 months of probation.

Blakey was nominated to the federal bench in 2014. He had long left Alvarez’s office by the time video was released of a white cop fatally shooting Black teen Laquan McDonald, the fallout of which led to Alvarez’s primary loss to Foxx in 2016.

During his Senate Judiciary nomination hearings, Blakey was asked to define his judicial philosophy. Fitting for a former theater student from a Catholic university, he spoke about playing his role, and paraphrased the New Testament.

“I would characterize my philosophy as a devotion to the law, a devotion to the role that we play in society, that limited role, but important role,” he said. “In a variety of contexts, a great deal of power is given, and to those who are given power, much is expected.”

mcrepeau@chicagotribune.com

jmeisner@chicagotribune.com

rlong@chicagotribune.com